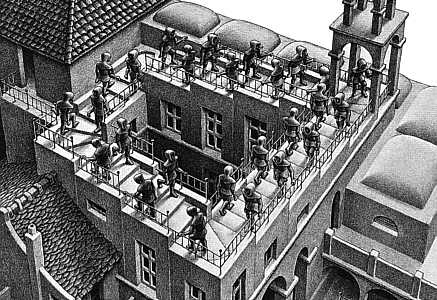

Those biomass power stations: how they might look

The problem with biomass power is that you can’t really say definitively if it’s a good thing or not. Biomass power is clearly a Good Thing In Principle, in that power derived from biomass should be low carbon, renewable and reliable – able to produce baseload and mid-range power continuously either in the form of new power stations or through co-firing or substitute firing in existing power plants. All good , economical and low carbon. The government certainly thinks so, which is why they are backing biomass power (electricity and heat) in their Renewables Roadmap as two of the eight technologies the Roadmap thinks will provide the lions share of the target of 15% energy from renewables we committed to achieving by 2020. Indeed one could say they are pretty keen, almost banking on biomass – midrange estimates of what they think production of biomass energy can achieve is almost 35% of the 234 terawatt hours of energy supply that will comprise the 15%. Later this year (yes I know it is later this year already) the Government is to produce a biomass strategy, it says.

That’s when you think about biomass in the abstract. When it comes to producing actual biomass on the ground, as it were, it gets a bit more complex. How large should biomass power stations be? Should their size reflect the availability of fuel in the locality around the power station, or should we be happy to import most of it? And if we do how can we be sure that what we are importing is really as renewable as we think? The problem with importation of biomass is not so much the extent to which its journey detracts from its low carbon value (not much if it is shipped is the answer) but on whether it arises from sustainable sources. The low carbon value of biomass derives, essentially from the fact that it is recycling carbon continuously and therefore producing carbon neutral power. If the biomass is stripped and not regrown, then the cycle doesn’t work and it is not really low carbon after all.

Then there is the actual nature of a biomass plant itself. If the government is aiming to produce quite as much biomass power overall as it requires to meet its share of the renewables target, then , presumably the ambition for heat and electricity (the Government suggests between 32-50 twh for electricity and 36-50 twh for heat) ought to be in tandem: plants should mostly be combined heat and power plants, for example. Having electricity-only biomass plants is again, dubiously low carbon because much of the product doesn’t result in power, but in hot air going up a chimney, just as conventional power largely manages to achieve. All this was the subject of seminar on the subject I chaired last week , bringing together a number of MPs and groups and individuals concerned about biomass deployment. A centrepiece on the table was the recent report from the RSPB on bio energy (summary here; full pdf here): interestingly, not so much a general treatise on the environmental effect of biomass supply and use, but a survey of what is happening to biomass deployment now.

The survey is really quite disturbing on the deployment front. For as we speak, more or less, massive amounts of biomass are being deployed, either in actual build, or in advanced planning proposals to do so. The RSPB effort, as far as I know is the first serous attempt to look at exactly what this consists of currently in the UK, what kind of fuel is being used or proposed, and what the production will be.

I don’t quite agree with the RSPB on their strictures about imported biomass. Providing it can be seen to be sustainable (and I accept we have some way to go on that) then low carbon energy is low carbon energy after that, and shipping it doesn’t detract much from its value. But what the report really does highlight is the rapid, rather random building of plants and conversion of others with , apparently very little regard for size or output. Size is, it seems a product of uncertainty about how the planning system will work in the future. Put in an application for a plant with over 50mw of electricity production, and then it will go to the Infrastructure Planning Commission (or son of) with ministerial approval likely at the end of the process. Whether that is wise as far as feedstock or a balance between electricity and heat output is concerned is another matter. A large number of the planned plants are above the 50mw output, sometimes massively so. They will clearly always have to rely on imported biomass for their supplies, and because they are gauged on electrical output, concentrate on doing that, and that only.

The report identifies 31 currently operating biomass plants, only 6 of which actually provide heat (I.e. are Combined Heat and Power Plants). The figures for planned plants are worse. Of 69 plants planned, only 12 are CHP. What seems to be happening under our noses as we await the biomass strategy document which will provide, presumably, a detailed plot of how we get our 40-odd terrawatt hours of renewable heat produced by 2020, is that large electricity-only plants are being installed across the country, potentially locking us into an industry that doesn’t produce the heat required, is energy inefficient, and hence not really very low carbon. Which I guess will not be such a Good Thing after all.

I hope the biomass strategy document when it comes out addresses this: if it doesn’t pretty urgently, then the words stable doors, horses bolting etc come to mind. We certainly can’t get to a meaningful target of biomass heat with a fleet of plants that don’t produce any, that’s for sure.